Southwest Sierra #66 — More on Forest Health

July 10, 2024

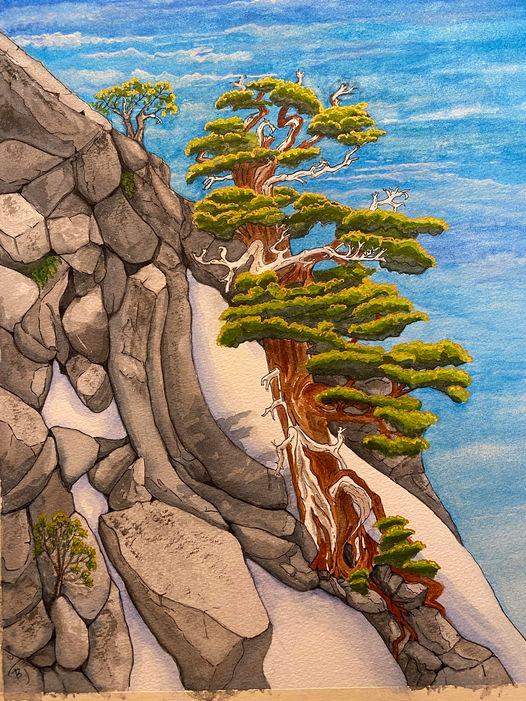

Juniper in the High Sierra. Watercolor by BJ Jordon.

In SS #63, I stated that “trees that get more sun grow faster,” but the day that it was published, I realized that statement is an oversimplification. I immediately thought of BJ Jordan’s beautiful paintings of those tough little conifers in the High Sierra that might take a century to grow an inch in diameter. What I should have said is: “Trees that get plenty of sun, have plenty of soil and adequate water grow faster than trees that don’t.”

Then Dan Guyer of Pike, who has been a carpenter for many years, and who also mills his own lumber, explained to me that faster growing trees (like the tree with less growth rings in the illustration for SS #63) make crappy lumber [slower growing trees make stronger lumber]. In all fairness, I should point out that the younger tree in my illustration only had 10 growth rings, whereas the one in Idaho City had 29. Dan also gave me a book titled The Redesigned Forest by Chris Maser Published by R& E Miles 1988. So far, I have only read the first part of the four-part book, but when I started reading it, I was surprised at the similarity in Maser’s and my way of speaking about nature. He talks about “we humans” with our limited perspective and the much, much longer cycles of nature that we know so little about. He writes the word nature with a capital “N”.

I appreciate how Mr. Maser articulates the thing about “good” and “bad” that I alluded to in SS #64 regarding dead trees. He puts it this way: “Nature is always neutral. We as humans, however, never have a neutral thought; we therefore assign values to Nature’s actions that are based on our perceptions of “good” and “bad.” While I don’t agree with his statement that “we humans never have a neutral thought”, I do agree with his observation that “Nature is always neutral”. Generally speaking, humans do assign “good” or “bad” labels to most things. This makes me think of the story of the Garden of Eden and how eating the “Fruit of Knowledge of Good and Evil” caused the expulsion of humans from the Garden of Eden (the Forest?). Food for thought (pun intended).

Mr. Maser uses a study of flying squirrels to illustrate the hidden connections and dependencies in nature. As explained in SS #35, flying squirrels are nocturnal, which is why we rarely see them. According to Maser, their habitat is mixed conifer forests from the arctic tree line, all the way down to Mexico. Their main food source is underground fungi fruit (think mushrooms that grow underground) and lichens. The squirrels also use lichens to line their nests high up in the trees.

It just so happens that many tree species depend upon underground fungi for nutrient uptake. This includes most conifers and many deciduous trees. The fungi attach themselves to the ends of the tree roots and absorb nutrients and water from the soil, making them more readily available to the host tree. The tree in return provides sugar from photosynthesis to the fungi. If you have ever dug a hole in the woods (to poop?) you may have noticed a layer near the surface that holds together in a mat-like structure? That is the underground fungi, the “mold” part of the fungi that is holding all those feeder tree roots together. This is where the symbiosis between the tree and the fungi is taking place. Its scientific name is mycorrhiza which literally means “fungus root.” This relationship between tree roots and fungi also aids the fungi in fixing nitrogen in the soil. Nitrogen is used by both the tree and the fungi. Healthier trees are more resistant to harmful fungi and other insects and diseases that tend to shorten their lifespan.

Mr. Maser helped conduct a Scientific study in the 1980s to see if the spores of the underground fruiting fungi (hypogeous fungi) eaten by flying squirrels survive in their gut. The study confirmed survival of the spores. Not only that, but the squirrel poop also contains yeast which inoculates the fungi spores. What this means is that each turd is a “magic bullet” of spores ready to grow whenever they land on the forest floor. This spreads the fungi that is so beneficial to the trees. The book even has a picture of squirrel turds in a petri dish. Now I’m thinking that all the flying squirrel poop that I cleaned out of my attic should have gone in the compost pile!

Featured Articles

Human Remains Found Near South Yuba Bridge in March Identified →

December 17, 2025

Authorities identify remains found in March as Aaran Sloan Taylor, seeking next of kin.

Transfer Station Burn Suspended After Community Concerns →

December 16, 2025

Sierra Hardware Plans Extensive Repairs After Flood Damage →

December 8, 2025

Sheriff’s Office Accepts $60,000 Grant for New Search and Rescue Team →

December 2, 2025

Confusion Surrounds Release of the Plumas County Grand Jury’s Report →

December 4, 2025