Forest Health Continued — Southwest Sierra #64

June 26, 2024

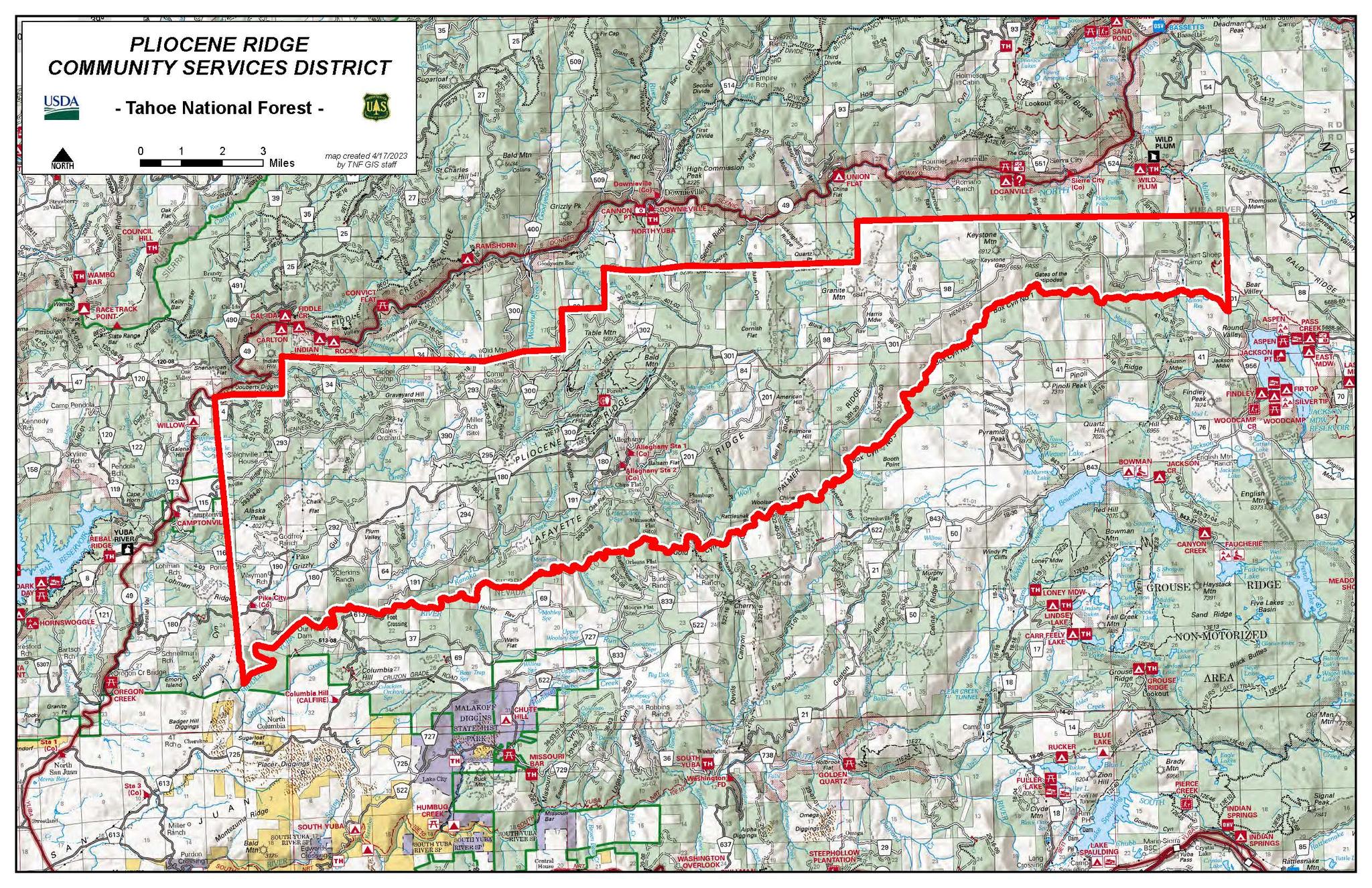

Map of Pliocene Ridge CSD that shows private land in white with public land shaded green. Note the top right hand corner where a true “checkerboard” exists.

Several years ago, my husband and I traveled through Deadwood South Dakota. While there, I was surprised to learn that the town got its name because of the many dead trees found there in the early 1870s. It is now assumed that a beetle infestation in the late 1860s caused the massive tree mortality. A gold discovery there, announced by General Custer in 1874, resulted in a rush of non-native people to the area. They named the town Deadwood, paying no heed to the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie that had deeded the land to the Lakota People.

My surprise at this tree die-off approximately 150 years ago, reflects an internal assumption that we humans are the cause of, well, almost everything bad that happens in nature! As the story above illustrates, this isn’t always the case. That land hadn’t been logged or mined before the beetles swarmed. The use of the word “bad” in the sentence above reflects an assumption that tree mortality is a bad thing. Last week, I explained how dead trees feed the forest, making it healthier, but as you can see, I harbor the same cultural imprints that make it difficult to recognize and trust nature’s cycles. It wasn’t until after that trip to Deadwood that I recognized tree die offs as a natural occurrence. I had heard that dead trees are good for the forest and had observed how the insects in the dead trees feed so many animals. The benefit of dead trees was recently confirmed when I learned of scientific studies that document forest biodiversity increasing exponentially with dead wood scattered across the forest floor compared to areas without it.

I doubt if a consensus can ever be reached on the best way to manage our publicly owned forests. Heck, members of my own family don’t see eye-to-eye on this topic. Efforts to defragment the landscape are, in my opinion, a crucial step in the right direction. I am referring to ongoing land swaps and purchases of private property by the Federal Government of parcels surrounded by public land.

On a larger scale, maps that show both private and public lands in our area look like a green and white checkerboard. It was explained to me as a kid that the white private squares were deeded to the railroads when Abe Lincoln was President. This was done as an incentive to push the railroads through. An older friend of mine once criticized President Lincoln for those subsidies and I assumed that Lincoln was the architect of that plan. I decided to research the topic of land grants to railroad companies for this week’s article.

As it turns out, the precedent for deeding land to railroad companies was established long before Abe Lincoln was President. The following information is quoted and paraphrased from the well-researched book Land In California by W.W. Robinson, University of California Press 1948. An act of Congress passed on April 30, 1802, provided the State of Ohio with land grants for the purpose of a wagon road. Many similar deals for wagon road and canal building in the eastern U.S. followed. Then, beginning in 1835 with the introduction of trains Congress made many grants of public land to railroad companies. [California was still part of Mexico at that time]. The push for a transcontinental railroad began as early as the 1830s but it was the California Gold Rush, combined with the succession of the Southern States that acted as a catalyst. According to W. W. Robinson, Congress and many others viewed the transcontinental railroad as a military necessity to hold the country together. “The Pacific Coast was defenseless, and the overland route was beset by dangers and Indians.” As such, it was the Secretary of War who was authorized by Congress to hire surveyors to find the best route from the Mississippi River to the West Coast.

The surveyors went to work in 1853, and in 1855 the War Secretary delivered his report to Congress. [Jan. 1, 1863 was the date of the emancipation proclamation]. The Pacific Railroad Bill passed by Congress in 1862 and amended in 1864 “empowered the Union Pacific Railroad Co. and the Central Pacific Railroad Co. to construct and maintain a railroad and telegraph line and to be the recipients of land grants. - The Union Pacific was authorized to build from Nebraska to the western boundary of the State of Nevada and the Central Pacific was to start at either the Pacific Coast or the navigable waters of the Sacramento River to the eastern boundary of Nevada, but each company was authorized to continue until they met” regardless of the boundaries mentioned above. The culmination of this effort was the ceremonial laying of a final railroad tie made of California Laurel and the driving of a golden railroad spike at Promontory Utah on May 10, 1869.

The golden spike is the part of this history that we are all most familiar with. Next week I’ll go into more detail about how the checkerboard of private and public land was worked out.

Special thanks to Hank Meals for pointing me to W.W. Robinson’s book. The book is available online at https://archive.org/details/landincalifornia00robirich/landincalifornia00robirich.

Featured Articles

Two Plead Guilty to Poaching and Animal Cruelty Charges →

December 30, 2025

Two men face penalties for illegal hunting activities in Sierra County.

Fish and Wildlife Plans to Collar More Deer, Elk, and Wolves →

December 30, 2025

DWR Conducts First Snow Survey of the 2025-2026 Season →

December 31, 2025

Storms Bring Heavy Rainfall and Local Disruptions →

December 22, 2025

Sierra Hardware Plans Extensive Repairs After Flood Damage →

December 8, 2025